Chapter Ten: Set Boundaries, They Said

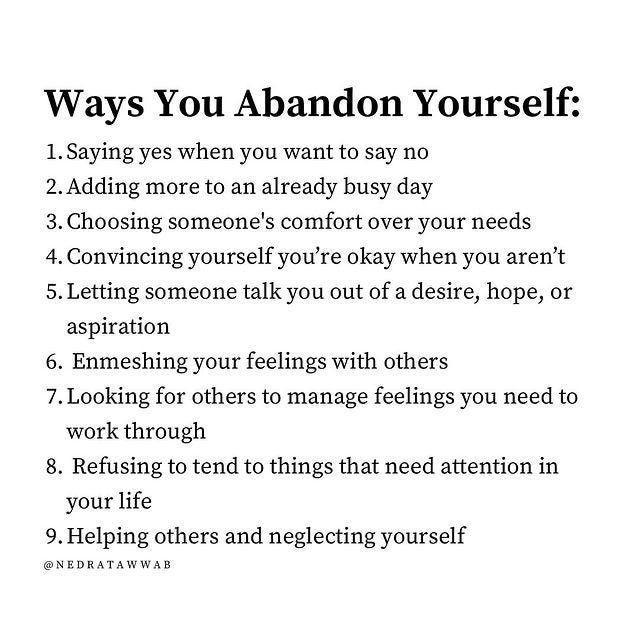

My book, Substacked chapter by chapter. You can read it for free.

I’m Substacking a book! You can catch up on the previous chapters under BOOK: Expanding Consent on my homepage.

It is free to read for all subscribers. Thank you for being here.

Chapter Ten

Set Boundaries, They Said

Bedtime is a tough time in our home. I lose patience as the day wears on, quite literally progressively shedding it so that by evening I’m left with a few miserly dangling bits of it. I live with a chronic condition so I get tired easily. And my children – well, they are also at their least patient in the evenings, in spite of being trainee night owls.

For years I tried to set a hard boundary with my son: I would sit by his bed at night for a few minutes, then walk out. For YEARS we tried. It occasionally worked but let’s just say that if this method had been rigorously tested, it would have been pronounced a failure and immediately discontinued.

But this was my boundary, I said to myself.

I saw boundaries in a very specific way: as a firm wall that we place between ourselves and others, and demand that others accept.

With time, I’ve come to believe that when we nurture relationships of love and trust, we do not need to build walls to protect ourselves from others. I do not see boundaries as firm walls – but as one of the ways we work together to get our collective needs met.

I want my children to know how to set boundaries when needed. I also believe that power dynamics matter here, and that the language we use around boundaries leads us to see them in a confrontational, rather than a relational, way.

What even are boundaries?

I define boundaries as the way we get our needs met. My child’s boundaries will be the expression of their needs and of how they’re hoping to get their needs met; and my boundaries will be the way I express my needs and how they deserve to be met.

So for all those years, when I was saying, “I can only sit with you for a while, then I will leave” to my child, what I really meant was, “I’m tired. I need to go to bed at a reasonable hour so that I can get the sleep that I need in order to be the human and mother I want to be. Can we find a way for me to do this, that also works for you?”

Boundaries are a way we express our needs out in the world, and a practice of self-consent and autonomy will lead to an expression of where our boundaries lie. Modeling boundaries shows other people that we can rest in our own self-worth, and shows our children that they too, deserve to do the same and be vocal about it. I used to believe that boundaries meant setting arbitrary limits and then cajoling others into respecting them: this is not the case.

I want to be clear: boundaries are not the same thing as limits. Limits are arbitrary rules we decide to impose on others. They don’t always have much to do with needs, and they often involve controlling other people’s behaviour.

Boundaries are crucial in consent because, for me, they are one way we can show our children how to relate with others in a consent-based way – boundaries mean that my child can practice ways to express their need for consent and respect, while also not controlling other people.

Those two aspects of boundaries are so crucial! One: getting out needs met, and Two: not controlling others in order to get our needs met.

Because if we are getting our needs met by forcing others to do as we wish, then we are standing up for our own needs but we’re trampling all over the other person’s, and that is not consent-based practice. Conversely, if we are overriding our own needs to get someone else’s needs met, that too doesn’t feel like consent-based practice.

Consent is a mutual, shifting, re-negotiable agreement, not a one-way street.

Here’s a real-life example (I got this framework for boundaries from Melissa Urban’s The Book of Boundaries, but the example is absolutely one from our own life!):

My kids are playing together and one of them is humming loudly. The silent kid asks them to stop because they feel it’s too loud. This is a request that the hummer might grant, but it’s not a demand. The hummer doesn’t HAVE to stop humming. The silent kid cannot force the hummer to stop, but if they don’t, and if it continues to bother them, they can say “I’ve asked you to stop and you’re not willing to, and that’s okay. But I’m feeling overwhelmed so I’m going to go read in my room now.” The silent kid didn’t force the hummer to stop, but they did set a boundary that reflected a need (and upheld their boundary by withdrawing from playing together).

Of course, this can transpire in all sorts of messy and complicated ways! The kids might decide to make an agreement around humming loudly in a shared space, or the silent kid might decide they will put up with the humming, or the hummer might stop humming quite so loudly – there are multiple ways to respect boundaries, and many of them aren’t tidy and scripted. There are ways to collaborate over a mutually desirable outcome, without having to set or uphold hard boundaries. But the point is that modeling boundaries and the ways we can uphold them while also respecting the other person, is important if we’re going to practice consent-based relationships and if we’re going to express our needs without controlling or manipulating others.

One important thing to mention here is that boundaries between siblings, or boundaries between adults, are going to look a lot different than boundaries between parent and child.

This is for several reasons: the adult-child relationship is inherently skewed, as we’ve seen. Adults hold a lot more power, AND concurrently the responsibility to safeguard our children. Those two concerns, and the line between control and safety, needs to be considered. The way I set boundaries with an aquaintance, will look different to how I ser them with my husband, and cannot and will never look like the way I partner with my children to get my and their needs met, and to keep them safe.

Because yes, boundaries to me, mostly look like partnering when it comes to my children. I want my kids to see me express my needs with other adults out in the world, and stay true to myself, and for that I will need boundaries (because society!). I want them to see this so that they know they are worthy of consent-based-ness out there in the world – they see what it looks like, so that they can stand up for themselves!

But when it comes to my relationship with my children, I choose connection and partnership as the way to get my needs met. Does this mean I have no boundaries? No, it does not.

It’s a beautiful, tricky, multi-layered dance and I’m going to talk a bit about it next.

Armour up!

I have done enough armouring to last me several lifetimes. I do not need my children to armor up around the people they are most comfortable with.

It wasn’t always like that. I was raised in a rather.. combative household, for lack of a better world. Confrontation was our MO. Nobody was holding their tongue or taking deep breaths. We said things. Sometimes in loud voices. We also protected ourselves.

I armored up for the world, because this was the way I knew, and because frankly, I needed to. Nobody was going to realise my apparent cool calmness hid a messy, sticky, sad core.

I did this as a parent too, for a while. I would reach a certain point in the interaction and then withdraw, harden my tone and set my limit – nobody was going to cross me after that. I scared my daughter, and frankly I scared myself.

I sometimes revert back to that but my children will tell me now. We’ve spoken about how sometimes my reaction is to close up. My daughter will now say, “You’re scaring us, mommy.” And I recognise what I’m doing, and quickly soften. I apologise, a lot.

Boundaries, if we take them to mean protecting ourselves from the people we love, from our own children, can backfire. Instead of connection they can bring separation, withdrawal. That is not the sort of boundary-setting I can get behind.

I don’t see boundaries as a protective mechanism, at least not in my relationship with my children. I want to be soft, open, vulnerable with my kids – not putting up walls that inevitably shut them out.

Back to the bedtime antics: at some point I recognized that my child’s need for company or comfort sometimes has to override my need for rest. Not always, but sometimes. That is okay, and that is parenting. Often as parents, our boundaries will need to shift and change, be less uncompromising, or simply be set aside for a while, because the needs of our child are greater, and developmentally crucial.

Leo is 10 now and I still sit with him at bedtime. I don’t set a hard boundary, but instead I express my need (which can be different on any given day), and collaborate with him to get both my need for sleep and rest, and his need for comfort, met.

Some days I sit for a long time, because he needs me to. Some days I only sit 5 minutes. And some days I fall asleep right by him. Bedtime is not a battlefield, but a place for partnership and conversation. (Okay sometimes it’s not all peace and love, we’re not perfect after all!). But mostly, I talk to him about why I need sleep. I talk to him about how some days I’m less tired and more willing, and others I am not. He tells me that he needs my body next to him at times, that he needs comfort. He will only be little for so much longer, I remind myself. Sometimes, my eldest needs me to sit with her too - and if I feel I can do that, I do.

But let’s not scrap boundaries altogether

I understand why some people might want to rid their parenting toolkit of the term ‘boundaries’ if it has caused them stress or harm or shame, and I worry about what it actually means to scrap the idea of boundaries altogether.

Like if we’re not calling boundaries that anymore, do we have another word? Are we still holding on to this concept, the idea of having needs and finding ways to get them met, which I believe is fundamentally a crucial one?

I worry that throwing boundaries out the window might mean our needs also get thrown out with them.

I think the issue here is two-fold: one, we lack a definition of boundaries that everyone understands and can get behind, and two, boundaries actually just exist out there whether we call them that or not, so we can decide to ignore them but we can’t actually scrap them.

We often confuse boundaries with limits - this is clear to me when I hear people using the terms interchangeably. They are not the same, and this is not just semantics: it matters.

Limits are arbitrary, often top-down rules. They don’t necessarily result from an understanding of needs, or from a connected relationship with our children, even though we are told that “children need limits to feel safe.”

Children don’t need limits. You may want to have some rules or limits, but they are not in any way a need. They don’t need limits to feel safe, or for any other reason; that is absolutely just a myth to control children and to legitimize adult power over. I am not in the business of promoting limits.

Boundaries, however, are entirely different. A boundary is a reflection of a need. Boundaries are ways that we figure out our needs, and find ways to get them met. That’s it!!

We all have boundaries because we all have needs. We can ignore both, but they will still exist.

You can’t give children boundaries

You cannot impose a boundary on others, because a boundary is about you and what you can control.

You cannot “give” children boundaries because boundaries are about OUR OWN needs, so all we can do is show children how we get our own needs met, and honor what children say about their own needs, and perhaps support them to find ways to meet their needs and make decisions around their own boundaries. We can also talk to them about the needs of others, and about what feels right and what feels wrong, and point out that those are boundaries they might need to respect.

‘Upholding a boundary’ is not about forcing or controlling others, but about doing something we can control to meet a need. I don’t love this phrase because it sounds like we’re barricading for an attack, when in reality, it’s not like that at all.

Here’s an example: My children are being loud, and I need silence to finish writing. I can move to another room, or I can use earplugs. None of this infringes on their autonomy, but it is a boundary I am setting: I don’t want to work in a loud room.

The place where it gets sticky in parenting I think, is what if your children follow you to the other room? This, for me, is a moment when consent and collaboration come in. We can have conversations around my need to work, and their need to be with me, and how can we get both needs met? In this sense, yes, we didn’t need a firm boundary because we collaborated to come up with a solution.

Sometimes we do need to express our needs as a firm boundary - both with our children, and out in the world. But in most cases, boundaries and collaboration are not mutually exclusive! In fact, boundaries are supportive of collaboration because they help us figure out ways to meet our needs.

My need was for quiet. The boundary was something I could control: leaving the room or wearing earplugs.

The collaboration piece was talking to my child about how we meet both our needs, even if this sometimes means allowing for flexibility around my boundary.

And that’s another misconception: boundaries need to be “firm”.

I don’t see boundaries as walls, literally set in stone. I don’t see consent as a wall either. Both are fluid, both take everyone’s needs and desires into account. Both are moving and always fluctuating and changing.

Both are about togetherness, not separation. We still need them.

But I worry that telling people we don’t need boundaries might actually translate to trampling over people’s (especially mothers’, carers’ and marginalised peoples’) needs, and that feels worrying and problematic to me, given women’s history of martyrdom and putting everybody’s needs before our own.

I think the language of boundaries, if framed as ways we nurture and care for ourselves, and ways we can work together with our children to care for everyone, is still helpful. I think there is even a place for co-creating more solid, communal boundaries for our families, so that we aren’t always negotiating around things moment by moment, so that we do have a framework that allows us ALL to feel held.

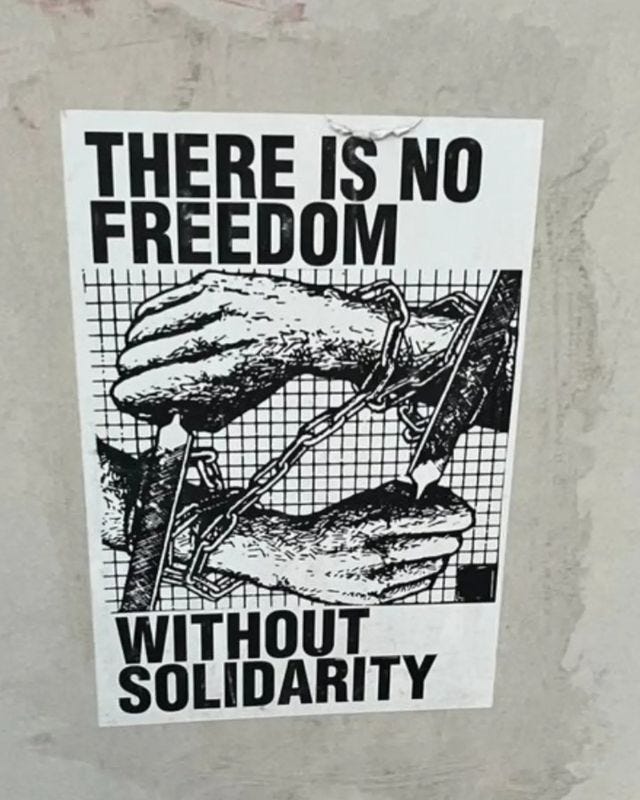

In the example above, I could also ask them to lower the volume, and they might decide to do that. We can practice being kind and considerate to one another - not every infringement of autonomy is an attack on personhood. Freedom, after all, is by definition bounded.

I also worry that telling people we need strong, firm boundaries, and that we as parents need to “uphold” them consistently, means we become inflexible, self-serving, and unable to be in partnership and community over everybody’s needs, rather than just our own.

Inflexible boundaries, as many of us with neurodivergent or PDA kids might have realized, just don’t work for many children.

Partnership, talking about needs, co-creating a framework of boundaries, does work.

The other piece of this is that there might be something we call “organic boundaries”.

My wise friend Sherene Cauley, wellbeing coach and founder of The Nurtured Life, speaks of “organic boundaries”: the boundaries that just exist. She speaks to the rather counter-cultural idea that we don’t exist to exercise power over, but we live in mutual, equitable relationship to everyone and everything around us.

Here is what it might look like: boundaries and consent (which are interrelated) exist out there. We have become socialised to unsee them; but they are there.

In her book Braiding Sweetgrass, author and academic Robin Kimmerer writes about the “honorable harvest”, which represents the Haudenosaunee and many other Indigenous American tribes’ relationship to the earth. Embedded within the guiding principles of the honorable harvest is a natural, inherent boundary. There is a sense of being in a consent-based relationship with the earth, one another, and ourselves. You only take what you need. You take with permission, you share, you give thanks. You respect the earth’s needs too. Those are invisible boundaries that nobody needs to uphold, they simply exist. Everybody is able to sense, feel and see them because they are already there. This same story, in different versions, is repeated in so many texts and oral traditions from a variety of cultures.

If we follow this idea through, we actually don’t have a boundary problem, and we aren’t “bad” at setting boundaries, because boundaries already exist. What we struggle with, what we’ve unlearned, is how to see, acknowledge and respect boundaries.

I co-wrote a post with Sherene some time ago, addressing this issue: that because boundaries actually exist already, we shouldn't have to get good at “enforcing” them. The problem is not us, being shitty at boundaries, but those who trample over boundaries that would be clear to see if only we hadn’t been taught to unsee them!

Fundamentally, the problem is patriarchy, industrialization, capitalism and all the systems of oppression (surprise!). They have made it so that the organic boundaries that were provided for us, became subject to a system where “might is right”, where extraction was normalised, and where power over became the norm. We learned to take and take and ignore the organic boundaries that governed our relationship to each other and the earth. We learned to use our power and might to overcome other people’s boundaries, and taught others to do the same.

Sherene Cauley writes:

“It’s not a coincidence that so many individuals seem to have issues having their own boundaries recognized and respected. It’s not a surprise that we try to have our needs met using the same methods as those who have crossed our boundaries. And, it’s completely understandable that we are unable to recognize and respect each other’s organic boundaries since we have very little experience in respectful relationships. We can start here. With this realization that the boundaries have been obscured. And, if we do that we need to accept responsibility for clarifying these organic boundaries. Not just for ourselves and our bodies, but for everyone.”

Because we still live under this systems, we need consent-based-ness to eradicate it and we need boundaries, in the meantime, to stand up for ourselves and in solidarity with our children. And perhaps this is my dreamer side emerging, but I want to believe we didn't always have to be so aggressive about boundaries. And that perhaps, we won’t always need to be. Perhaps, a combination of recognizing people’s needs, respecting organic boundaries, and collaborating with our children - is what we really need.

Letting go of boundaries altogether risks us releasing ourselves from our needs, and becoming unable to see the organic boundaries that are already in place. I worry it might also mean that my children won’t learn to see the silent, invisible boundaries that are already present in relationships, and also might not learn to sense their own internal needs and boundaries.

The answer is never as simple as, “We need boundaries” or “We don’t need boundaries”, as much as we might want it to be. (We can however, trash the “children need limits” narrative!)

And also, it’s personal too. Some of us might need a new word for this concept, because the word boundary has gotten too tied up with arbitrariness and limits and rules, and that is of course okay. Some of us may need to simply reframe boundaries.

The concept itself, though, is worth preserving - because in some ways, it has always existed.

Thank you for reading!!

Next up.. Chapter 11 on trust - a bit one for me, and perhaps for you too!