Does excluding under 16s from participating in social media, actually protect them?

We still want children to be seen and not heard.

Update on the state of my Substack: I’m once again re-newing paid subscriptions. I’m going to try and post weekly, but shorter pieces. WISH ME LUCK. And THANK YOU if you are still supporting me on here. I appreciate every single one of you. (And if you can’t afford a paid sub right now, pls reach out and I’ll barter or comp you)

On November 26, Australia’s parliament passed a law that bans children under 16 from being on social media.

Plenty has been written on why this is either a good or a bad idea, and this isn’t a post about that. Although I thought this was a pretty good recap:

What I AM here to do, is to write more broadly about whether bans in general are a good idea and whether they work, as well as to point out some ironies.

This particular news is relevant to us, because we might start to see some of our own countries follow suit and bring in bans or restrictions.

What young people actually think

A few days ago I did an Instagram poll, and asked people to message me their thoughts, and so many things came up. Many parents seem to not be super keen on their teens being on social media, but also don’t support banning it outright. I think I sit in this place too. I worry a blanket ban will penalise those who really need social media (marginalised youth, for example), while also making it way more dangerous for young people to get on social media - because while some might be relieved about being banned, some might take it upon themselves to find roundabout ways to stay on SM. Banning it makes it more enticing, right? This seems likely to lead to even more dangerous usage, because kids will tend to hide it from the adults around them.

One of the most surprising things I’ve discovered during my research is that there are young people who support a ban. And yes, there are many who do not, of course, but that’s unsurprising to me - I want to talk about the ones that do.

This is specially interesting because a 2022 study found that only a minority of teens from 13 to 17 years say that social media has had negative affects on them or others, and are more likely to say it is a positive thing than a negative thing (although they do acknowledge some of the tough parts of being on it). Roughly half of teens interviewed support criminal charges for people who bully or harass others, or a permanent ban for these people. They were not asked about a blanket ban for everyone, but based on the study’s foundings it doesn’t seem likely teens would find this helpful.

However, I’ve also heard the flip side of this. Granted, these stories are mostly anecdotal from young people or their parents, but I’ve seen that some teens experience a sense of relief at not feeling pressure to engage with social media. The decision has been taken out of their hands! Some teens say they feel safer, and that this is overwhelmingly a good thing because children and young people are in fact very savvy and knowledgeable about the internet and they have often either experienced or seen how things can go downhill or have adverse effects. (To an extent, the 2022 Pew Research Survey I mentioned above, reflects this anxiety, and a 2023 study about usage also reflects how all-consuming SM can be for some teens, but it’s interesting to note the differences in demographics here and what they might mean).

What this tells me though, is not that therefore we need to ban SM for all teens. This tells me that some young people feel out of control and unsupported in their SM (and possibly wider internet) usage, and that we, the parents and carers, need to step up and support them. It also tells me that the onus of making SM a better, safe place should land on the corporations mining us for data, rather than only on us. The 2023 study also seems to indicate that for marginalised youth, SM is a safe haven of sorts, hence the more frequent usage by Black, Latino and lower-income teens, and by girls compared to boys.

What this does NOT tell me, is that banning it for everyone will solve the issue. But let’s talk more about the issue with blanket bans in general.

Do bans actually protect children?

Banning things for children is not new. This most recent ban follows a well-established pattern of adults enacting bans over things that are either known or perceived to be potentially harmful for some children.

I am not here to argue over the evidence, or lack thereof (although the evidence is in fact, inconclusive and not causal). I believe we all have the right to make this sort of decision within our own families and communities, whether it’s based on evidence or not; I am a lot less sold on the righteousness and effectiveness of a top-down ban, which should be based on evidence.

The US’ history of book banning is well-documented. Much like social media, book bans are pretty easy to circumvent, and have generally been focused on schools and libraries. Which is not to say that bans aren’t harmful, usually to the more marginalised and under-resourced children.

In 1982 the Supreme Court ruled that banning books from school libraries violated First Amendment Rights. So technically, banning access to information is a violation of these rights. The reality is that a lot of parents, elected officials and school boards don’t see this decision as binding, and carry on doing what they decide is best. The difference is also that these are not always bans that are passed via legislation, and they are usually localised.

Book bans are different to a national social media ban, but there are some similarities. Proponents of banning social media and phones might claim that while book bans are motivated by right-wing political agendas, social media bans are different because they are motivated by evidence showing that SM access is responsible for a crisis in teen mental health. But in fact, both book and phone and SM bans are often couched in the same, or similar, language of protection. Protection from “the gay agenda” or critical race theory, or from harm to mental health, all end up sounding very similar in the end.

And this particular ban in Australia, is extremely political. While it was championed by groups claiming they were protecting children and supporting parents, it is fundamentally a measure that targets a specific group of people (teens) and restricts their access to information, entertainment and socialisation. Crucially, it doesn’t do anything to actually provide an alternative “third space” for teens who rely on SM for connection to be around others.

The logic is that if teens are off social media they will somehow magically go back to.. frolicking in the woods, perhaps? Playing in.. oh wait, teens don’t really have a whole lot of spaces to spend time in, to be independent from adults but also safe. I think banning a place where teens virtually spend time, and not providing the sort of structures and places for teens to hang out, is an issue.

Can we learn from phone bans in schools?

Regardless of whether the ban is truly protecting teens, bans simply don’t have a history of working.

To be clear: I’m not saying that social media for under-16s is a good idea for all children. I am not sure it is! One of my children is a teen and she is not on SM yet. She hasn’t wanted to be, and we’ll be talking about it when it comes up.

What I am saying, is that a top-down, blanket ban on something teens crave and arguably some teens need, might seem like the right thing to do, but historically we have no evidence that it will actually work - it may not work logistically (teens will find ways to circumvent it, as they have always done with banned things), and it might now work in terms of outcomes.

One similiar example might be the way some schools have enacted phone bans in recent years. This has tended to happen in waves, first in the 1980s and 90s and more recently in the early 2000s, and it has happened all over the globe. A review of 22 phone bans in schools points out that the banning of devices usually happens after politicians and the media amplify what they perceive to be a social worry, “creating moral panics about issues for which little-to-no evidence exists - and to which banning then becomes a seemingly necessary and politically popular response” (Campbell et al., 2024).

In other words, banning starts to feel like a good political decision, rather than a measure that will actually contribute to children’s wellbeing. (Side note: because if we really cared about children, many Western nations could do relatively simple things like lift people out of poverty, provide free or affordable housing, provide children with free meals, make healthcare affordable or free, and so on.)

I was really curious to find out whether some recent phone bans actually worked. If we’re going to be banning technology, we should probably have evidence that the positives of banning outweigh the negatives, and that banning can actually be enforced. Phone bans appear to be easier to enforce because they tend to be carried out by individual schools, so are much more localised. (We should note though, that the reason they “work” is that schools are allowed to use coercion and completely ignore children’s rights in ways that workplaces for adults would never get away with).

In terms of outcomes of the bans, the study mentioned above looked at the effects on academic achievement, student wellbeing, and rates of cyberbullying. The evidence about academic achievement is really mixed, and overall inconclusive; it sometimes improves achievement, for some kids, but there is no difference or sometimes lowers achievement for others.

The evidence around wellbeing was more conclusive, in the sense that there doesn’t seem to be any causal evidence of phone bans in schools affecting a change in mental health and general wellbeing (although one study found that not having access to their phones was a source of anxiety for children). Cyberbullying research was mixed: some studies find less bullying when phones are banend at school, some find that there is more victimization in schools with restrictions around phone usage.

The researchers found some evidence that phones are actually a valuable learning resource, and that not having access to them impacted learning negatively. I chatted to a friend who gave a perfect example of what a blanket phone ban in schools might do: a friend of hers works in a school where phones have been banned from classrooms, no exceptions. The way this has impacted this particular project-based classroom is that children aren’t able to look things up, follow online tutorials or view images online, all aspects of learning and completing their projects. Kids aren’t even allowed noise-cancelling headphones, which has affected those who need them to stay regulated in class.

In the case of phone bans, it seems the bans do sometimes work in the sense that schools were able to force children to abide by them or deal with serious consequences, although we have some emerging research that suggests that actually this process didn’t always work and some kids still managed to circumvent bans. On the other hand, phone bans didn’t work in the sense that there is no conclusive evidence that banning or restricting phone usage in school has inevitably good or bad effects, and there is some evidence both anecdotal and “scientific” that actually, bans can have negative impacts for some children.

With this in mind, I think that banning social media for teens across the board, although very different to phone bans in schools, is nothing more than a potentially dangerous experiment. Dangerous because unlike schools, social media companies will have to figure out how to enforce the bans and this is something we’re not sure they’ll be able to do; and dangerous because there will likely be other hidden costs.

Hidden costs

I have no evidence for this, but here is something I’ve been pondering: when the government steps in and starts to regulate screen usage at home, it actually has the potential to undermine the connection between family members. Some parents might find it a relief that they can now invoke the law. But I think seeing it this way only reinforces the way we normalise curbing young people’s autonomy, and are thrilled when the government seems to be enabling us. It reinforces a dynamic where we the parents and caregivers feel we need the backing of the government in order ‘lay down the law’ in our homes.

We should ask ourselves why we feel the need to relate to young people this way: by invoking the law, but also by setting arbitrary, top-down limits as if that is the only way to protect our children.

And while I recognise not every family has the sort of time and resources to build a daily connection where we talk and discuss and partner on big decisions, and on the ways we spend our time - I can’t help but feel like that should be the focus.

Supporting parents to have the time and space to build connected relationships with their teens might be way less popular and more expensive as a policy (because it would involve things like talking about a Universal Basic Income, parental leave, better pay), but ultimately it could do so much more than a blanket ban.

One hidden cost of the ban (and of all bans and restrictions that target children), might be the erosion of trust between children and their caregivers and adults in general. It might actually make teens less safe, especially if they are also losing connection to their online communities.

Children are still ON social media

Lastly, the greatest irony is that the social media ban isn’t really a social media ban - it’s a participation in social media ban. Children are still very much present on SM, just passively or mediated through an adult lens. In other words, teens under 16 are unable to actively hold accounts and post content, they are denied autonomy and participation in social media, but there is little to no moral panic when it comes to the images of children being shared online, or children being used as content (sometimes for the profit or benefit of their parents, or other adults such as businesses promoting their service of product.)

The ethics of posting pictures, videos and identifying information about children on SM are fuzzy, and there is definitely a spectrum in terms of the ways adults do this and whether they are gaining anything from it (followers, sponsorships, etc). But as of right now, there is no far-reaching regulation around the ways parents share about their children online. The line is drawn at parental consent - which leaves us, the parents, with a lot of power.

As someone who used to share pictures of my children’s faces, and now includes them in posts and videos only very rarely, and always with their consent, I have definitely been in a place where I had to ask myself whether using children as content sat right with me. I’m not only talking about their actual appearance, but also about sharing their stories online.

I think we need a much broader conversation about children’s presence on SM, possibly even more urgently than the one about children participating in SM.

Seen and not heard?

How weird would it be if women were banned from using social media, but men were still posting pictures of women, including them in their videos, profiting from their possibly nonconsensual presence online?

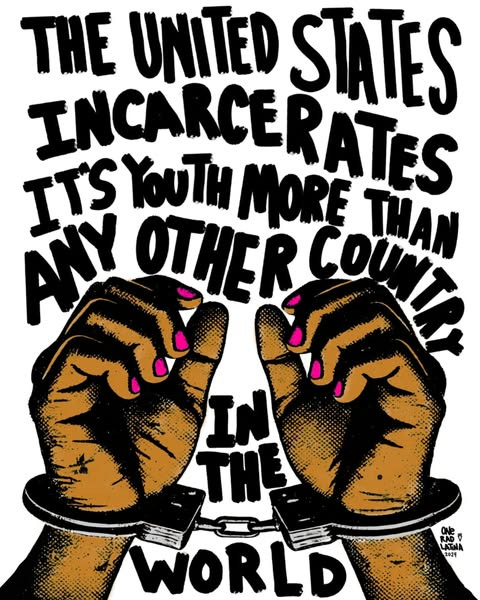

For all intents and purposes, a ban renders children voiceless on social media. We are able to see them there, but they aren’t able to actually speak up - unless mediated through an adult account. They are a passive, quiet presence - the kind of presence adults tend to like. Is this another version of “seen and not heard”?

And sure, under 13s cannot use social media and yet we see them on it all the time. This is still not okay.

Connection v. banning

I am not necessarily for blanket bans, in general, unless we can prove the thing is uniformly bad (which we really can’t in the case of social media).

But I do think we need to have conversations. We need to educate families and young people on what it means to participate online. We need to respect our children as people, and make sure we have their consent when sharng their image or their informaiton. We need to stop using children as content, especially when it’s for profit. We need to sit by our children as they start to understand social media.

Any legislation that concerns children should also consult children and young people. Is is their right, enshrined in the United Nations’ Convention for the Rights of the Child (UNCRC), and it also makes sense that the concerned group should be consulted before legislation that affects them (something that was not done for the recent Australian ban). Children’s right to participation are not less important than their rights to protection and provision - but they have tended to get less air time.

It’s a lot easier to “protect” a child who has no way to voice their opinions, and that is why we need children to be involved in policies that affect their daily lives.

Thanks for reading people! This was meant to be a short piece, but here we are..

Next week, look out for Chapter 12 of my book, which I’m currently working on getting published eeeek!!

Sending you all love,

Fran x

References:

Campbell, M., Edwards, E. J., Pennell, D., Poed, S., Lister, V., Gillett-Swan, J., Kelly, A., Zec, D., & Nguyen, T.-A. (2024). Evidence for and against banning mobile phones in schools: A scoping review. Journal of Psychologists and Counsellors in Schools. https://doi.org/10.1177/20556365241270394

It’s great to see you writing again Fran!

You know me Fran and you know what I'm going to say here: anytime any institution is enforcing behaviour, its an abuse of power. The book bans are an apt comparison but what about abortion bans? Bans against gay marriage? While the context of control is worth considering, governments placing any restrictions against a subset of people immediately raises red flags for me.