How my children learned to read as consent-based, self-directed people

And some thoughts on trust and reframing literacy

Before I get into it, I wanted to share a project that means a lot to me, and the team at The Alliance for Self-Directed Education. So many dedicated people have been working hard to develop a resource for the community that will support us all on our SDE journeys - after more than a year of work with over 60 creators and the support of The Vela Foundation, they have launched The ASDE Compendium: a rich collection of knowledge, wisdom, and lived experiences from practitioners of Self-Directed Education (SDE) around the world.

This is not just a resource—it's a vibrant community of learners, educators, and changemakers who believe in the power of Self-Directed Education for social change and upending oppressive systems.

The first guided co-hort will launch on April 12th!!

I am taking part in it and would love to see you there! If you’d like a preview of the platform and to learn a little more, check this out

To be clear, this is not an affiliate link - I volunteer for ASDE and believe in their mission :)

Last week, someone asked me how my children learned to read as unschoolers, and I promised I would share more.

I’m going to split this piece in various sections, feel free to scroll and read the bit that interests you the most.

First off, if you’d like a deeper dive into the available research around how children learn to read, its pitfalls, gaps and what we can learn, go check out my post about learning to read, the unschool version.

In this post, I will share some of the following:

personal account of how my children learned to read - one of them as an unschooled child, the other with a combo of home ed & Montessori preschool

trusting our child to learn in their own time, and supporting them as and when they need us to, are not mutually exclusive

thoughts on literacy and neurodivergence: is reading overrated?

reframing literacy

thoughts about why i don’t believe in decentering literacy

How they learned - unschool to Montessori

I still remember P picking up one of the books I’d read aloud to her hundreds of times, and declaring that she was going to read it. Then, she would proceed to ‘read’ the book, almost verbatim, except it was all from memory.

Part of me wanted to say, “Don’t guess, try to read!”, but also, we both knew she wasn’t decoding the letters and sounds (which is one aspect of reading), but she was reading in the sense that she was telling a story and understanding the words!

She went from ‘reading’ books in this manner, to actually decoding the words and fully reading, in perhaps 3 months? She had just turned 6 and she was ready.

P was at home with me until around she was 5.5 years old, then went to a Montessori pre-school for a short while, and that’s where everything clicked in the span of a few months.

Technically, she didn’t learn in a self-directed way, although her experience at home provided a ton of invisible scaffolding; at age 6 she was 100% ready and willing to learn - in fact, desperate to learn! She wanted to be able to pick up one of our books and read the words. She didn’t want to be read to anymore - she wanted to do it herself.

I could have just let her figure it out, and eventually she would have, probably. In hindsight, up until age 5.5, I was incredibly hands off - we read aloud a lot, and generally lived an engaging and engaged life, but we didn’t do any intentional reading work at all. I basically waited for her to show signs she was ready - and that coincided with her going to preschool.

She is the child that actually enjoys direct instruction from adults, and so once at preschool she did really well following the Montessori method, which I highly recommend if you have a child who responds well to structure and a really gradual, well-scaffolded method that is also child-led and can be done on your child’s timeline.

Unschooling doesn’t mean we just sort of leave them to it! Sometimes it does - because sometimes that is what our child wants and needs. But other times, it absolutely can mean following a method, if our child is willing and they enjoy it.

P is now an extremely proficient reader. She is self-directed BECAUSE she can read proficiently - that is how she gets the vast majority of her knowledge and skills, and how she achieves many of her goals.

She has written several stories, is working on a book, has written plays and is currently writing a screen play with a friend. I would hazard to say that self-directed education, for her, is highly dependent on her reading and writing skills.

This, of course, is not the case for all children. But I think it’s important we recognise that it IS the case for some, and that those children get the support they need.

How they learned - “by themselves”

My son was an entirely different kettle of fish.

He refused any and all attempts at trying to offer materials, activities, workbooks, explanations, even games in order to help him with learning letters, sounds, phonograms and eventually reading.

The key takeaway for how he learned was that I kept offering things, and some things stuck, but only for a short while. Then I was back to waiting, perhaps offering something new, perhaps just shifting focus for a while, and on and on for YEARS.

I don’t think ALL kids necessarily need phonics instruction - however, I do think it can be helpful to have a very basic understanding of phonograms because a) it will come up in learning to write too and b) it can really help put the pieces of reading together more quickly, especially if the child is eager to ‘get it’ and c) it’s not gonna hurt (unless you’re forcing them, in which case it will probably do more harm than good).

I took my child out of school age 5, and he was not reading. Honestly, he had very little interest in learning to read. He loved to be read to, and that was okay with him.

We went through SO many different phases with his reading, mostly because he is extremely demand-avoidant (probably PDA) and so I basically kept suggesting new things and never expected anything to stick beyond a few days or weeks - the combination of demand avoidance and novelty-seeking can be SO tough, and I recommend people buckle up and just ride with it.

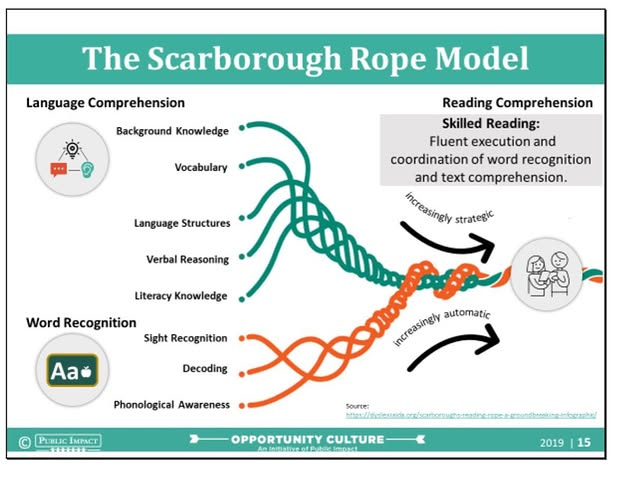

In hindsight, his seemingly haphazard way makes complete sense: reading is not only about learning to identify letters and sounds, and decode words - there is so much more (see the Reading Rope model above!). And while it’s tempting to want learning to look linear and tidy, in reality it looks like picking bits of all of the elements of reading from a variety of sources - from books to video games to conversations to play. Eventually, it all comes together - just because we don’t see it coming together, doesn’t mean it isn’t happening!

Some things we did regularly:

I read aloud

we listened to audiobooks, a lot

I would point out writing wherever we went

I let go of learning the alphabet - what’s the point? instead I focused more on learning the sounds of the actual letters. We played games I made up that involved the actual sounds of letters - this is SO much more helpful than learning the name of the letters or the alphabet in order, that will come later.

I had magnetic letters we would play with

I made a point of identifying phonograms (if he was open to it): phonograms are the letter or letters that make up a sound. So for example, the letters c and h together, make up the sound ch. Some children who are never taught phonograms explicitly, will simply pick them up from reading, speaking and living in the world. Some children might need more explicit instruction - we don’t actually know the amount of homeschooled children, who are supported to learn at their own pace, that still require explicit instruction; we have data of schooled children but like I mention in my other piece on reading, there are issues with applying this data to all children, universally. That said, if your child is open to explicit instruction, why not support them with it? I will say that my son was mostly not receptive to me mentioning phonograms or giving him bits of advice around reading - however, if I felt it might help, or if he asked, I would offer it.

we played - this is probably the biggest thing. We made up worlds and stories and narratives. We made up jokes and puns (like me, he’s partial to a good pun). Everything children do in play is preparing them to understand what your home culture and the broader culture values and requires of them - all of play is preparing them to be literate, we just don’t recognise this enough.

Some things we tried for short periods of time:

reading eggs app

we did various kinds of spelling games - there’s no reason to separate reading from writing!

we had a couple weeks of tracing funny sentences I wrote using tracing paper - credit to

for this ideawe tried a few of the Reading without tears and Writing without tears books. They were short-lived but hey, they were fun for a while

I made flash cards with words on them - I started with phonetic words and moved onto words with similar phonograms in them - and we would do things like I would flash a card, he would read the word and then jump off the sofa/do a trick on his scooter/ jump on the trampoline 10 times, and then repeat.

We played lots of Kids Scrabble - this wasn’t super helpful with reading but it did help with recognising letters and their phonetic sounds

In the end, it really is just about waiting, keeping on supporting them in ways they will let you, not stressing that they are 7 or 8 or 9 and can’t read, and trusting it will happen. It is about not needing to control the process, but knowing that it is happening, we just don’t necessarily see it.

The disclaimer to this statement is this: sometimes kids don’t want support but they perhaps have learning disabilities or challenges that require support. This is super tough, but I would never advise a child with dyslexia to just wait and see and let them figure it out - they won’t. Learning to read should not be about dogma - instruction is absolutely okay, if needed, and no unschooling coach or person should be saying it’s not (in my opinion!!).

That said, if you don’t suspect any learning challenges, waiting is okay. If your child really wants to learn but it feels too hard or they don’t want to be taught (both of those things were the case for us), then perhaps they need support with things like regulation rather than reading support. We had many conversations and a lot of practice because there were several things that were getting in the way of practicing reading regularly:

my child WANTED to learn how to read. However, at the time he really struggled to regulate his emotions in situations where he felt he was not succeeding immediately. We had to do a lot of practicing and talking about the ways our brains work: how our brain needs to feel regulated in order to learn, how our brain needs to practice things over and over again before succeeding, how every time we work on something we get a tiny bit better even though we might not notice it, and so on. SO MUCH OF LEARNING TO READ WAS ABOUT THE FOUNDATIONAL WORK OF LEARNING TO STAY REGULATED, KEEP TRYING AND BE KIND TO OURSELVES. I’m emphasising this because often we don’t talk about how this needs to happen before children, especially neurodivergent children, can feel ready to tackle challenging things.

A lot of it was about relatedness (being in connection with me), autonomy (feeling like they weren’t being controlled) and mastery (feeling supported to improve) - the pillars of self-determination theory.

some children are just not ready to follow a timeline that someone else made up on the basis of the average child (which by the way, is no child at all). We need to allow for this. I believe he was 8 when it finally clicked - when I say ‘clicked’ I don’t mean that he could suddenly read all the words; it’s that he could stay calm and focused enough to read Dog Man and skip over the words he didn’t know, rather than give up. It was still slow, and gradual. Not an overnight thing at all!

Learning to read it not a final destination: it’s a continuum. L never wanted to read the early reader books because they were super boring. He wanted to read the books he wanted to read! And so of course that took an extra level of skill that he developed very gradually. At 8 years old he was reading Dog Man very slowly, leaving out the hard words, and sounding out words painstakingly. As we read, I would occasionally remind him about things like what the sound of “ch” is, or that when there is an “ing” at the end of the word it sounds a certain way, and so on. Essentially - phonograms. But we did them while actually reading, and only if I sensed he was receptive and it might help him with future words.

Now, at almost 11, he still enjoys reading Dog Man except he can read all the words, he follows punctuation details and makes voices for all the characters. It’s the same book but oh so different. He’s moved on to much more challenging reading, like the Percy Jackson books, but is still very much partial to graphic novels. He still likes to be read to. And he more recently enjoys reading to me. He has become a confident reader, and is also comfortable asking me how to pronounce difficult words, and pointing out when phonograms appear, or when the pronunciation of a word isn’t what you might expect.

In terms of writing, I’ve learned a lot from the way he learned to read and I’m WAY more chilled about his writing! We have all the time. I don’t try to make him write things, he will usually write when he finds a purpose to write.

For example, when he’s chatting with a friend online, when he’s making a list of things to do on Zelda, when he’s creating a game for us to play together, or ranking his race cars by speed and various other markers. We do no structured writing practice at all - I’ve tried a few different ways to do this and nothing ever stick. And, I noticed that when I stopped offering, he found his own ways to practice writing.

No one child

The reason I am often in two minds about sharing how we do xyz is because self-directed education is a multiplicity of experiences. There is no average self-directed or unschooled child, there is no reading curve or program for self-directed children, and even the research we do have emphasises how diverse learning is for children who learn at home. There is no proof that it always works, but also there is tons of proof that it often works, to partner with children around the best ways to become literate.

Does this mean we sit back and trust? Look, I know people will tell you that they sat back, trusted and their child was fine, but perhaps they trusted AND they also provided a lot of support. Trusting and support are not mutually exclusive.

Gina Riley did a study of grown unschoolers and how they learned to read, and Harriet Pattison wrote a book on how home educated children learn to read. One of the main issues I have with the phrase “learning to read” is that what does it really mean? Did the child become a proficient reader and writer? Are they fully literate in multiple ways? A lot of the research and blog posts on homeschooled or unschooled children don’t actually answer this question fully.

Pattison suggests viewing reading as a cultural practice rather than a cognitive skill. In my view, it can absolutely be both. Yes, it can be trasmitted rather than explicitly taught, given the right environment and a degree of time and autonomy; and, it can also be taught like any other skill. My concern isn’t so much how children do it - there is no universal way! But more about putting children in a position where they are able to do it at their own pace, in a consent-based way.

We can trust in our child’s abilities, AND recognise that it’s okay for them to need help, AND acknowledge that they have a right to provision too - they have a right for us to be there, supporting and providing resources when they are needed.

Self-direction should never feel like a burder to a child - it should feel like a right to make decisions, and a right to also be cared for and supported.

If you’re looking for more, this is a good starting point for things to do that are not curriculum, and this is a thoughtful account of child-led, consent-based learning to read. I wish I could remember our process in this much detail!

Literacy & neurodivergence: is reading overrated?

I came across a paper recently, that essentially put forward the idea that our conversations around literacy should not be so obsessed with reading; what the author meant is that making meaning can happen in many ways, and that’s what literacy is really about. Literacy is about extracting meaning from content or experience, and this can be done in many different ways, not only by reading.

The author writes that a true inclusion of neurodivergent and disabled experience would decenter reading and open literacy up to broader ways of accessing information, of knowing, of making meaning. They propose we engage in something they label ‘neuroqueer literacies’, which would reframe “literacy… to reference all meaning-making, whether gleaned from conventional phonetic texts or not. In this way, a focus on literacy broadens our expectations for where meaning can be found, who can find it, and how they might do so. Neuroqueer literacies refine this focus by drawing our attention to particular, embodyminded modes of meaningmaking that we have left under-appreciated.”

How do we feel about this?

I have a child who loves to read, but also loves to make meaning and gain knowledge from a variety of other means - play of all sorts, podcasts, music, observation, audiobooks, documentaries, video games, and so on. All of this is literacy! He is making meaning every single day, and so he is literate in the most expansive meaning of the word.

Although I am partial to reading and writing, I hope that in our home I have never put reading on a pedestal above other ways of gaining and processing information, and I hope I have never placed writing above other ways of communicating and creating meaning.

What does it mean to achieve proficient literacy? Does it HAVE to centre reading/writing?

While I believe that literacy is crucial, I am in two minds about whether decentering reading/writing is something we should be proposing.

Literacy, in a basic sense, is the ability to read and write. When the US government talks about literacy rates - they mean people’s ability to read, write and comprehend what they read and write.

But actually, the idea of multiliteracies is gaining ground. UNESCO defines literacy as “a continuum of learning and proficiency in reading, writing and using numbers throughout life and is part of a larger set of skills, which include digital skills, media literacy, education for sustainable development and global citizenship as well as job-specific skills.” The NCTE affirms this definition, and proposes expanding literacy beyond just reading and writing (much to the horror of several other organisations - literacy has gone woke!)

And yet, in most schools and even home education conversations, we come back to a narrow focus on reading and writing. I have very mixed feelings about this, actually, and I don’t pretend to know what we should all be doing.

On the one hand, decentering reading and writing makes sense. The superiority of these means of gaining and communicating knowledge intentionally excludes children and groups of people whose ways of being and knowing do not centre reading and writing. Putting reading on a pedestal serves to marginalise those who do not gain proficiency in reading and writing. It sets standards that intentionally exclude, and perpetuates them through systems of schooling and education and assessment.

On the other hand - I live in the real world and I want my children to live in the world, too. Reading and writing is crucial to gaining knowledge and engaging with everyday life. And, I recognise that reading and writing was historically withheld from certain groups of people, like women and enslaved people in the US, and therefore literacy that centres around reading and writing is a form of liberation for some. It would be extremely privileged of me to discount this, and to go around saying we should be decentering it.

I think this can be a case of both/and. I can recognise that the supremacy of reading/writing is marginalising for many, AND I can also recognise reading to be a tool for freedom and autonomy.

I can recognise that the narrow definition of literacy is baked into harmful systems like schooling, neoliberal education policies and capitalism, AND I can also recognise that we all have to exist at least partially inside of those systems, while working to build alternatives.

I want my children to be literate in many different ways, AND I also would like them to be proficient readers and skillful writers, to the extent that they are willing.

What about “decentering literacy”?

Look, if you wish to raise your children to decenter reading and writing I have nothing to say about that - I get where you’re coming from. If you wish to decenter literacy altogether - hmm, nope. As discussed above, literacy can be reframed to include all sorts of ways of being and knowing. That is the work we should be engaging with.

I recognise that there are so many ways of existing and making meaning that are routinely unacknowledged by Western schooling systems and by Western society - I am ALL FOR recognising that children learn in all sorts of different ways and that they all matter. I am ALL FOR living and learning as if school were not a thing, as if imposed ideas of what learning matters and what doesn’t, were not a thing.

And, at the same time, I live in a very specific cultural context, and in my current context literacy, especially the elements of reading and writing, but also other types of literacy like media literacy and digital literacy for example, are crucial.

I believe that for my children, for who they are and the future they are likely to have, it’s going to be a real struggle if they are not proficient readers and writers, AND also proficiently literate in other ways.

Ultimately, I have a lot less control over what my children learn than I think I do. That said, I hope I will open as many doors to them as I can, and that I will take a degree of responsibility to provide them with the tools they might one day need.

Thank you for reading! Please share this post if it was helpful, it’s free to read.

Lots of love to you all, I appreciate you being here.

This really resonates! I felt this in my bones before I could put it in words, and have had to fight real hard to keep the pressure off of my son, who sounds similar to yours - including make my own mama cry. It’s hard to do as a single parent with little unschooling support. But my kid made her cry again when overnight, he started to love writing - because he figured out he could write swear words 🤣

“Mom, look” *shows me a list he’s written of all the swear words he knows that he’s picked up mostly from my friends with colorful vocabularies*

“Ermmm… well…” *have a fight with myself in my head for a minute* “… that’s nice… by the way, fuck has a silent k at the end of it and asshole has an extra s to make the long a sound and a silent e at the end to make a short o sound.”

*writes the list again with correct spelling* “Thanks mom!”

First time I remember being thanked for giving any sort of instructions/corrections 😅

Feels like it’s perhaps his way of taking control of (and literally saying fuck you! to) what’s been forced on him. Do I keep leaning into this to help teach him meaning, context, and discernment, or am I setting him up to be the potty mouthed kid on the playground all the parents want their kids to avoid?

Fran, thank you so much for this article! Mine are 4, and we are just exploring home/unschooling. This reads like a helpful map