I wrote a book about consent and consent-based living, and you can read it here chapter by chapter. Catch up with other chapters under BOOK: Expanding Consent.

Chapter Thirteen

Consent as Sovereignty

There is a thread I’ve woven throughout this book, and it’s that there is no universal child, no one way a family should look like, and as a result you may be disappointed, or relieved, or perhaps a little bit of both, to know there is no one way to do consent-based-ness. To do consent in practice.

I can only speak to what I have learned from others, from my work with children and from my research, but most of all from my own lived experience and from living every day alongside my children.

Preservation of personhood

Consent on a personal level is, fundamentally, ownership over ourselves. It is sovereignty. Is it inhabiting our own autonomy, and feeling free to say an authentic yes, no, maybe.

It is “preservation of personhood” in the words of my friend and fellow unschooler, Meghan Davies. Researcher Priscilla Alderson calls this preserving children’s integrity or wholeness. To me, these are different ways of saying the same thing: our children are born whole and sovereign, and we can partner with them to maintain that.

In this chapter I will talk about what I broadly call consent as sovereignty. I will talk about all the many ways that consent looks like in practice. All the many ways we can rely on it to preserve ours and our children’s personhood.

Because consent is, ultimately, a practice. And it looks so many different ways.

Authentic, or embodied, consent

This kind of consent is less about collaborating, and more about supporting children in their decisions and choices around their sense of ownership. It is less about getting community stuff done, or keeping a community running smoothly, and more about our young people having power, agency and autonomy to stand up for themselves, to make decisions about their bodies, their minds, their education, and their lives.

You will see that in practice, it’s actually impossible to separate authentic consent from collaborative consent or any other form of consent – life isn’t that tidy! But for the sake of creating distinctions and deeper understanding, I’ve separated the two here.

Authentic, embodied consent is born of autonomy, self-worth and connection. There are at least some instances, and perhaps many, where we will want to see authentic consent. Usually it is around the things that matter to your child. Is bodily autonomy their Most Important Thing? Then you’ll be looking for authentic consent there. Is ownership of their time important? Authentic consent is the way to reclaim it.

I use authentic and embodied interchangeably or together, because I’ve grown to understand consent as an experience that is both in line with who we are (our sense of authenticity) and in touch with what we feel or intuit (our embodied self). Both things matter.

Authentic consent IS embodied – it takes into account our connection with our body, our inner sense of knowing, our intuitions and emotions. Some people call this “enthusiastic consent”, and that might work for you too, although I feel like it doesn’t go to the core of what this is about.

When educators and psychologists talk about enthusiastic consent, they mean that when we say yes, we really and truly mean it. I’m not sure the word ‘enthusiastic’ goes far enough to explain how you can be fully behind consenting to, for example, getting a haircut, and yet not necessarily be enthusiastic about it.

What does it look like?

So what does his sort of consent look like?

Authentic, embodied consent looks like a person doing something because they truly want to, because it aligns with their inner sense of who they are, their intuition, their deeper knowing, with what they need and desire, with how they want to show up in the world, or with their values. It is a wholehearted yes, no or maybe.

Why do we care again?

I want learning and living to be this, for my children, as much as possible. Embodied, joyful, authentic. Wouldn’t it be a dream if we all could aim for this in our daily lives?

The reason I care so much about this, is because I felt such an echoing absence of it for so long, and for so long I couldn’t put my finger on what was missing. Was I unable to stick with things? Was I indecisive? Was I shy, weak, simply not talented enough? Was I lazy, perhaps? Or too much of a perfectionist? I didn’t know.

I didn’t know that I was whole, and worthy of remaining so. I’m not sure anyone around me knew that about themselves, or me, or others, either. We were all, not to be trusted.

And so that eventually took me here – to the full-body experience of authentically consenting. Authentic consent – navigating it, figuring out how to practice it, was my way to fill that absence.

It was my way to know intuitively, deeply, that it is a yes. To know, with so much certainty, that it’s a no. To recognise fully that often it’s maybe - that I need more time to consider something, that I’m not quite ready to know.

Authentic does not mean individualistic, separate. We all live in a context of some sort and we are all, to some extent, part of one another – both in a literal sense (atoms vibrating) and in a metaphorical sense (we cannot NOT be influenced by our culture, place, people). But we also have a sense of inner knowing that is both stable, and fluid. And that’s what I care about most.

I care that my children learn to hear theirs. I care that I learn to become connected to mine. I care that we all reach deep into our own unique sense of knowing, which is also, in some way, connected to everybody else’s sense of knowing.

This is the kind of consent we most often talk about – the consent that is rooted in our sense of worthiness and belonging. The consent that affirms who we are, and our claim to staying true to ourselves. That comes from deep, loving connection with ourselves.

Authentic consent is about what we believe we are worth.

What do we authentically consent to?

I can only speak for myself, my experience, my children and my family, but these are some of the things that I hope to see authentic, embodied consent around, in my home – the list could potentially be endless so I’ve reduced it to a few main things, and separated it into bodily autonomy and mental, spiritual emotional autonomy (although as we discussed earlier, these are actually very much woven together).

It gets tricky, because every family has different ideas over what ‘counts’ as ownership for children and young people. As far as I’m concerned, anything that is about their sense of self, their body or physical presence, their thoughts, feelings and beliefs, needs to have an element of authentic consent - because that is what I would want and expect of my own body, thoughts, and beliefs. I have the same standards of ownership for my children as I have for myself - we are both equally human.

Bodily Autonomy

The food we put inside out body: As someone who is recovering from disordered eating, and also was raised in a culture where consent around food was routinely violated, this is so crucial for me and potentially an utter minefield! But in principle, we might consider supporting our children to make embodied decisions around what, when, how and why they eat.

Ellyn Satter’s Division of Responsibility paradigm says that our role as carers is to provide the food, and our child’s role is to decide what to eat. In other words, we shop for and prepare the meals, we offer the food, and that’s where our job ends. It’s not our responsibility to make our child eat, to decide what and how much they eat.

This is seen as a dynamic model, that evolves as our children become more developmentally ready to perhaps helps us shop for food or make food themselves. It’s not perfect, and there are larger critiques to it such as that it is still gatekeepy and restrictive of young people’s autonomy, but I know it’s helpful for some.

While DOR worked well for us when my children were younger, we then moved into a form of self-direction around food, in the sense that we collaborate around the food we buy and where we buy it, we make meal plans together or at the very least with everyone’s preferences in mind, and I encourage my children to take as much ownership of sourcing, buying and preparing of food as they are willing to.

Another piece of why we could consider backing off from controlling what our children eat, is the idea of body neutrality and the way that diet culture impacts our decisions around food.

Virginia Sole-Smith, author of Fat Talk, defines diet culture as “the whole set of systems and beliefs that teaches us that a thin body is the best body. It's deeply connected to, and a byproduct of, white supremacy. It’s baked into our larger institutions and systems, our public health communities and initiatives, the way food and weight and health are talked about in schools.”

Body and food neutrality is a movement that invites us to look at all food as morally neutral, and all bodies as good bodies. This ties in with consent because when we stop labelling food as good or bad, and when we start to see all bodies as desirable and good, we remove a lot of the shame and emotional language we use around food, health, fitness and body size.

This means our children are able to truly practice embodied consent, based on eating what their body is telling them they want and need, eating when they’re hungry and stopping when they’re full.

The clothes we wear: The DOR paradigm can be useful here too. When our children are babies we’ll be in charge of supplying them with clothing of course, but our job is also to notice their preferences and accept the clothing they wish to wear.

What you need ot know about me is that allowing small children to choose clothing, as an Italian, truly amounts to a form of resistance! Italians are all about what you’re wearing and whether it’s correct or incorrect (and yes, there is an incorrect way!). I still remember when toddler Phoebe chose to wear bright pink leggings and a bright red jacket to the park one day, and my parents could barely look at her without cringing.

The point I’m trying to make is: it is our children’s job to choose what to wear. Yes, it is also our job to provide clothing options, and this might look like picking out clothes or like taking our child to the shop to choose them. But ultimately, it is their responsibility to actually decide what to wear - not ours. If they ask for advice, I provide it. If they don’t - I shut up.

Does it mean we never ever comment? Nope. My child had a phase around age 3 or 4 when he never wanted to wear his jacket even though it was cold outside. I asked once, and if it was a no I accepted it and brought the jacket with us anyway, just in case he got cold.

In all of these embodied decisions, there is nuance and context, and there is also, still, collaboration.

Taking care of our bodies: ranging from hygiene to the products we choose to put or not put on our body, to the ways we take care of our spiritual and mental health, this is a biggie.

How can we allow our kids to decide when to shower or brush teeth? Wouldn’t they choose to literally never do either?

The key to authentic, embodied consent is knowing your child, knowing your specific family and values, and trusting both yourself and them to come up with something that works.

And while I strongly lean towards not forcing our children, and towards honouring their sense of ownership over their bodies – this doesn’t mean we cannot have a discussion, we cannot put systems or rhythms in place, we cannot collaborate to make things happen.

The key is figuring out what really matters to you.

For me, it is daily toothbrushing. I would like it to happen most days, ideally every day at least once.

I recognize toothbrushing is a pain. I hate doing it and I’m 43! I still read my kindle or listen to something to get me through those 2 long, painful minutes. I also know it’s necessary and I will find creative ways for my children to get through it.

We’ve cycled through all sorts of phases to get Leo to brush teeth. Singing songs, playing games, watching 2 minute videos, me sitting by his toothbrush for upto 30 minutes, reading my book, just waiting. It has truly been a roller coaster. He is 10 now and he still struggles but it’s easier. He has learned his own tricks to get him through it. For years he only brushed his teeth once a day, and now on most days, he will brush morning and evening. Some days morning aren’t going to happen, and I let it go.

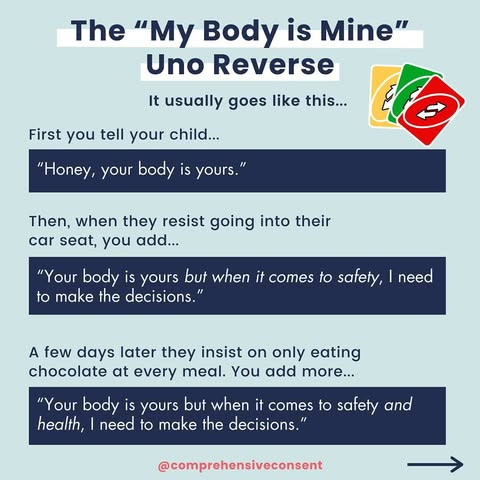

I know many of us struggle with things like showering and toothbrushing and our children’s resistence to it. It’s a big grey area for me because while their body is truly theirs, and I want to support that, my children are also my responsibility and I need to ensure their safety and care. Sometimes taking care of our bodies is not going to look like authentic consent, and that’s okay.

Physical touch : this is a place where we really need to understand the importance of our children having authentic, embodied consent over how they are touched by others.

I talked earlier about how feeling that your body is your own, and expecting those around you to honour that, is setting our children up to understand what kind of touch feels safe and consensual, and the sort that does not. It sets them up to expect the former, and call out the latter.

I think we need to think hard about the messages we’re telling our children when we manhandle them into their clothes, say nothing when a relative hugs them, and generally touch their bodies in ways we would never do if they were an adult friend or acquaintance.

The places they go: Bodily autonomy means we also get to have a say in where we take our body. The same goes with our children. As always, there is nuance here and it is extremely personal – but I think it’s worth mentioning that children and young people should participate in decisions around where they get to take their bodies, whether they want to go or don’t want to go.

Appearance: Hair styles, piercings, make up, clothing, jewelry, and so on – what we choose to do to our body, what we choose to wear or have on our bodies, with the understanding that we are not causing ourselves or others harm – is for us to decide. Our children are no different. As always, there is an element of safety and a responsibility of care that needs to be considered - and this will be really personal to every family.

Mental, spiritual and emotional autonomy

Our emotions: Children and young people have a right to what they feel, to inhabit and own their emotions, and to find ways to experience and express them. They should be able to feel seen, heard and emotionally validated by us. This is mutual, of course: we also should feel able to do the same. But of course as parents, we are tasked with holding our children’s big feelings while also not burdening them with our own.

So many of us find this incredibly difficult, myself included, perhaps because we don’t actually know what this looks like, or we never experienced it ourselves. This is where we can look into healing parts of ourselves, while also finding ways to break cycles of dismissal and unempathetic caregiving.

It’s not easy!

It’s also not only our job. It is not okay that it still is disproportionately women doing this “emotional labour”, in sociologist Arlie Hochschild’s words. It’s also not exclusively individual work, to do in the isolation of our nuclear families. This is collective work.

Marek Korczynski’s studies around the emotional labour of service workers point to the importance of “communities of coping,” in other words ways that we can do “collective emotional labour,” to quote Hochschild, rather than seeing this kind of work as individualistic, as something we should be doing and coping with alone, as yet another thing we should be striving to be good at.

Yes, it is inner work, but it is not work we need to do in isolation. Mothers, parents and carers deserve to be supported and in community while we figure out how to care for our children respectfully. Our own sovereignty also matters, just as much.

Thoughts and beliefs: My children get to experience consent around what they think and believe, even if it deviates from what I think and believe. They have ownership of their own minds, and throughout the years I have tried to step back from jumping in to correct their thoughts and opinions, and instead approached them with curiosity.

It is a careful balance between being honest with them, and sharing my thoughts and ideas – but also not attempting to take over theirs.

We have normalised things like conflict and disagreement and we are always working on being able to have conversations even when we radically disagree. This has not been easy for me. I take things personally, I’m probably too sensitive, and I love being right! I tend to want to say what I want to say, and it’s hard for me to know when not to say it. And – I’ve also worked hard on facilitating open-ended discussions, on listening, on not jumping in with judgment or criticism. It is all a work in progress.

I carry ‘lead with curiosity’ around with me for these moments. I say ‘I wonder’ a lot, rather than, ‘But it’s not like that!’ I try to model this in my life with family and friends, and in relationship with my husband - the latter of which is tough because we disagree a lot!

The things we’re interested in: We all hold very specific ideas around what things are worth doing and what are instead a waste of time. These are “schoolish” notions, in Akilah S. Richards’ words. They are assumptions that we learn from living in society and that are embedded in and perpetuated by our school system, but also go way beyond that. They are often colonial, capitalist, patriarchal notions that we bring with us through life, unquestioning. We learn that time must be spent, not wasted; that being productive is a good thing; that being of service and of use to someone or something is also key; that some subjects are worth learning and others are not; that some ways we spend time are superior to others. Playing video games for 2 hours is infinitely less desirable than playing outdoors for 2 hours, or working on Math problems for 2 hours. We don’t really question why that is – we just assume it’s true.

Honouring consent also means there is work for us all to do on deschooling, or deconstructing, many of these notions: recognizing they are constructs, challenging where they come from, and asking ourselves whether they are really true.

This won’t look the same for all of us of course, but it may lead us to recognize that the choices our children make about what they are interested in and what they don’t care for, conflict with what we grew up believing.

The ways we define ourselves: Respecting consent may also mean we honour the ways our children want to show up in the world, the ways they see themselves and wish to define themselves. It requires a radical re-shifting of our ideas around young people being “ours” rather than them simply being in our care for a short while, but fundamentally being their own persons. Teresa Graham Brett writes eloquently about the way our children are not actually our property, and the way we have used language to claim that we somehow own them, when of course no person can own another person - there is a name for that.

Our children belong to themselves. And as such, we may guide and advise and support them, but we will never have the final word on who they choose to be and become, how they choose to define themselves, how they choose to be part of the world.

We will never have the final word on their ability to consent, in the broadest sense of the word; they will negotiate their own mutual agreements and show up in relationships and spaces as their own people, not as humans we possess.

The how, when, where, why and what of learning: In principle, if we are respecting our children’s ability to say yes, no, maybe and to enter into agreements, then this needs to extend learning.

What if we took a leaf from the body neutrality community and leaned into learning neutrality?! This would mean we see all learning as morally neutral: neither good, nor bad, just learning. If all learning is neutral, then it follows there is no hierarchy of learning, no hierarchy of subjects or interests: everything we are interested in, all learning, all skills and pastimes, are valid.

I put this to you because I think shifting to a paradigm where all learning is valid means we can let go of some control over what our children learn - it means that their interest in Pokémon is just as valid as their interest in chemical reactions or poetry.

The people we are in relationship with: If our children are their own people, they get a say in who they are going to be friends with or associate with. This doesn’t mean we as parents have no say. It just means that we cannot pick their friends for them, and that they should be able to make decisions around who the people they spend time with are, which groups to join, who they feel comfortable with and who they do not.

The list above is not exhaustive. There are so many aspects of sovereignty that will shift and change as our children grow.

There are so many instances where individual autonomy bumps up against the needs of the collecive. Lately Leo and I have been talking about the way he uses certain spaces in our home that are, in theory, communal. Does he get to spread toys all around the house? In theory, he has autonomy over how he plays. But his freedom to play is curtailed by so many other things, such as our need to clean the floor regularly, to not trip over toy cars, to have some spaces in the house that are not taken over by games, and so on.

Yes, he has ownership over what he gets into, but there are always going to be limiting factors because that’s the nature of freedom when everyone is free. Where to draw the line is always so interesting to me. Where does one person’s bodily autonomy end and another person’s begin? Where does Leo’s autonomy overreach ownership of his body, and become an invasion of someone else’s sovereignty? When do we move out of the realm of sovreignty over ourselves, and into existing in community?

In the next chapter, I’m going to write a little bit about what the day to day practicing of consent might look like when we live with and around other people.

Thanks for reading! I’m curious to know, what are your Most Important Things when it comes to consent as sovereignty? What do you, and your children, feel strongly that you need to have ownership around?

Tell me below ;)

Fran x

References.

Korczynski, M. (2003). Communities of Coping: Collective Emotional Labour in Service Work. Organization, 10(1), 55-79. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508403010001479

Hochschild, Arlie Russell. The Managed Heart: Commercialization of Human Feeling, Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012. https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520951853

Graham Brett, Teresa. Parenting for social change.

The question of where the boundaries lie in terms of sovereignity is indeed so interesting. For me it is when it impacts negatively on the collective, such that the individual is also impacted negatively. At the stage my children are at, I need to be able to look after things like cleaning in order to be able to look after them. So if toys being everywhere is getting in the way of that, then we need to find a solution that means we can have free play AND the house does not become a health-hazzard. Equally, if my time is taken up doing all the domestic work, then I will have no time to play with them, and they would like me to play with them. Ergo I think the wellbeing of the collective takes priority over individual sovereignty, but within that, ideally each would have as much sovereignty as possible, if that makes sense. What this looks like in practice will depend on the individual make-up of any group - the ages, abilities, interests, priorities etc - and as such there are no hard and fast rules.